Student Blog: Michaela Coats

Home Hunting for Black Abalone

Entering the real estate market is not an easy process or a decision that one makes lightly. It takes years of research, competition, and compromise before a potential buyer eventually reaches the point of purchasing a home. What location best suits their needs and desires? What is the list of demands that they want in a home? How competitive is the market and what is the buyer’s budget? Overall, one must answer: what is the right house for them to turn into a home? It can be an intimidating process, but more often than not, potential buyers are not alone. Perhaps they are trying to find the right home for their family or maybe they seek out advice or opinions from friends. Either way, they likely have a real estate agent to guide you and act as a representative for their interests.

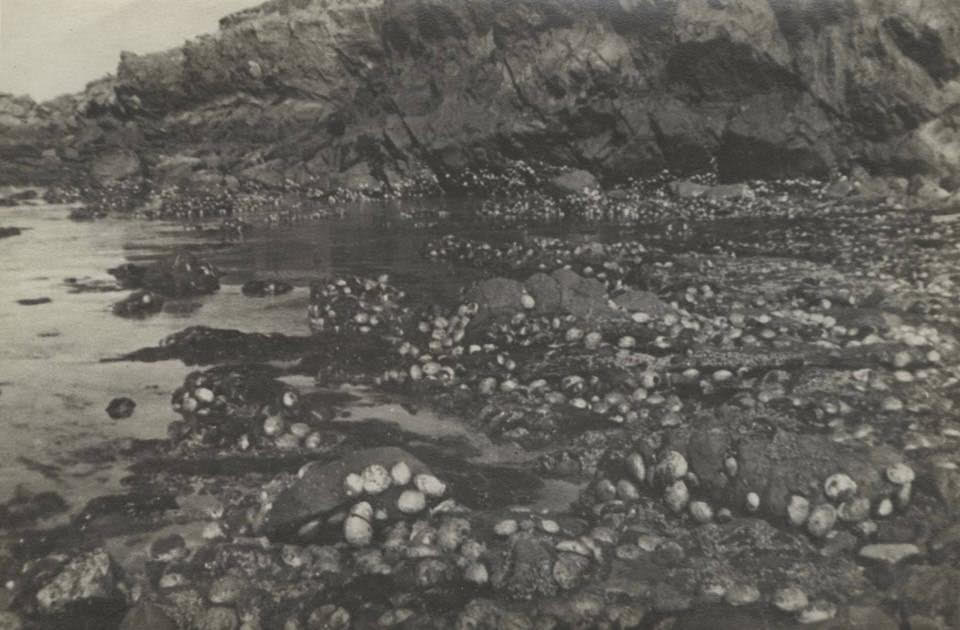

Through my Capstone project, I am acting as a real estate agent for black abalone. Black abalone (Haliotis cracherodii) are a species of marine gastropod that live amongst the rocky intertidal shores between Point Arenas, California and Baja Tortugas, Mexico. Being one of seven species of abalone found on the west coast, this group of kelp-eating molluscs has left a mark on the fisheries, diving, and indiegnous cultures of the region. The rocky intertidal shores were once abundant with dense communities of abalone and contributed to a multi-billion dollar fishery. However, in the late 1980s, black abalone underwent severe declines throughout the majority of their range.

The decline of black abalone can be attributed to both fisheries overexploitation and the spread of a disease called Withering Syndrome. Withering Syndrome is a pathogenic disease that leads to abalone mortality in one of two ways. Firstly, this disease directly degrades the digestive system and inhibits the production of digestive enzymes resulting in physiological starvation (Crosson et al. 2014). Secondly, it causes the muscular foot to atrophy resulting in lethargy and increased predation rates as Withering Syndrome inhibits their ability to adhere to rocks (Crosson et al. 2014). As a result, their populations plummeted, with over half of their range experiencing declines of 80-90%, eventually closing the fishery in 1993 and being federally listed on the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 2009.

For the past 12 years, black abalone have been one of two abalone species to be federally protected under the ESA. The other, white abalone (Haliotis sorenseni), have been listed since 2001 after suffering the same twists of fate as their black relatives. While the decline of these species was slowed/halted due to the closing of their fishery and subsequent listing, the recovery process for abalone is quite particular…

This is because abalone are broadcast spawners, their gametes are spewed into the environment in hopes that egg and sperm meet. While most other mobile species travel and explore their neighborhood or seek out a partner, abalone are more homebodies moving very minimal distances from the comfort and safety of their home. This means there needs to be a minimum density of individuals to have a fair chance of successful fertilization (Babcock 1999). The required density of adult abalone varies amongst researchers, but estimates generally fall between 0.15-1.1 abalone per m2 (Neuman et al. 2010, Tisscot 2007). Because of the severe population decline within subpopulations, this factor is a significant roadblock to the recovery of abalone species, greatly limiting their reproductive and recruitment rates.

To accommodate their reproductive requirements in this recovery process, researchers aim to have black abalone follow in the footsteps of their seasoned relatives by being captively bred and subsequently outplanted. Replicating the environmental conditions that trigger spawning is no easy feat, but great advances are being made in the overall breeding process. Before they are moved from their cozy lab out into the real world, the recovery team has to know where to move them. As such, my team and I are “house-hunting” for black abalone throughout the Orange County coastline.

To be a successful real estate agent, we must first know: what are the demands of our potential buyers?

The Right Size

Abalone nestle amongst the cracks and crevices and underneath boulders as a mechanism of protection. They prefer these home scars (the area where abalone reside and feed for long periods of time) to be small enough to be protective and cozy, but large enough to accommodate for growth and potential company. In order to evaluate potential “homes” for this aspect of their demands, we are evaluating the area of cracks, crevices, and boulders via randomized transects to help us understand if there is enough suitable space for a community of abalone to thrive.

Proximity to Resources

While some individuals may want to find a home that is far from the hustle and bustle of cities, my clients are homebodies and need their food close by. Black abalone rely on kelp as a food source and prefer giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) and feather boa kelp (Egregia menziesii). This kelp can be either growing in-situ or drift in from offshore kelp beds. To assess potential neighborhoods for its availability of resources, our team is collecting data on the presence/absence of kelp species and are conducting a remote sensing analysis of the variability of offshore kelp beds.

Friendly and Helpful Neighbors

My clients are additionally interested in a home with friendly and helpful neighbors. Interactions between coexisting species in the intertidal zone have been found to enhance or degrade the recruitment of black abalone. For example, some neighbors such as crustose coralline algae are welcoming and help enhance the chemical cues that induce settlement (Miner et al., 2016). Others, such as sandcastle worms, commandeer all the space and are quite unwelcoming to new neighbors. Therefore, we are estimating the percent cover of such organisms that are present in the best potential homes (crevices) at each site and recording the abundance of predatory organisms, such as sea stars or octopus.

Safety

Lastly, our clients do not want to move into a neighborhood or city with high crime rates. Humans are frequent and often destructive visitors to intertidal neighborhoods and while some have better intentions in their visits, others participate in more illegal behavior such as poaching. Although we are house hunting in regions that are Marine Protected Areas, strong enforcement of those rules are ultimately what would keep them safe. To accommodate this aspect of our client’s wishlist, we have been conducting human impact surveys in each neighborhood to look beyond how many tourists does this neighborhood see, but see what they are doing while they are visiting?

Our clients have an extensive and specific list of demands for their future home and compromise will likely have to be made. Therefore, to compare the neighborhoods amongst each other, the previously listed factors will be categorized into positive, negative, and neutral for each site. These categorizations are based on standardized metrics or standard deviations and will be cumulated to provide an overall score for each site, or potential neighborhood. The highest ranking neighborhood(s) will then be recommended as potential homes for black abalone populations to safely recover and return as an integral part of our rocky intertidal neighborhoods.

References

- Babcock, R. and Keesing, J. (1999) Fertilization Biology of the Abalone Haliotis laevigata: Laboratory and Field Studies. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 56, 1668–1678.

- Crosson, L. M., Wight, N., VanBlaricom, G. R., Kiryu, I., Moore, J. D., & Friedman, C. S. (2014). Abalone withering syndrome: Distribution, impacts, current diagnostic methods and new findings. Diseases of aquatic organisms, 108(3), 261-270.

- Miner, M., Altstatt, J. M., Raimondi, P. T., & Minchinton, T. E. (2006). Recruitment failure and shifts in community structure following mass mortality limit recovery prospects of black abalone. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 327, 107-117.

- Neuman, M., Tissot, B.N., & VanBlaricom, G. (2010). Overall Status and Threats Assessment of Black Abalone (Haliotis cracherodii Leach, 1814) Populations in California. Journal of Shellfish Research, 29:577-586.

- Tisscot, B.N. (2007). Long-term population trends in the black abalone, Haliotis cracherodii, along the eastern Pacific coast. Unpublished report for the Office of Protect Resources, Southwest Region, National Marine Fisheries Service, Long Beach, CA.